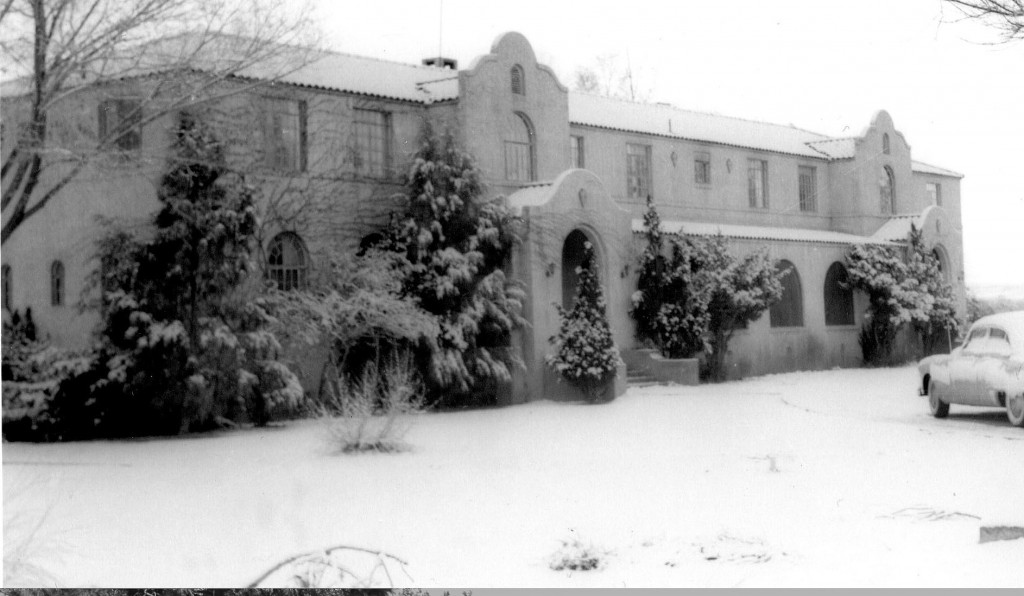

The remaining Albuquerque Indian School building, the Employees’ Dormitory and Club, is cast in distinctive California Mission Revival Style. This distinct architectural fashion, represented by bell towers, cool, dark, arched portals, fountains and shady nooks was popularized by nostalgia for “old mission days” as expressed in the novel ‘Ramona’, by Helen Hunt Jackson, and by other media designed to attract tourists to the exotic Southwest. Two Hollywood films of Jackson’s book and similar tales communicated the symbolic style to the world, making it synonymous with the Southwest.

Albuquerque had prominent mission style buildings. The famous Hotel Alvarado, by Fred Harvey and the AT&SF Railway, opened to much fanfare in 1902 replete with Harvey Girls and a museum quality Native American display and sales building. Its sister edifice, the YMCA, sat across the street, and provided rooms for railroad workers as well as various community programs. Both buildings were lost to the decline of Albuquerque’s downtown and its subsequent Urban Renewal program.

The Employees’ Dormitory and Club, still standing on the AIS campus, is one of Albuquerque’s only remaining California Mission Style public buildings. It is a testimony to the unique character of this school. Unlike many other boarding schools, students genuinely loved their experiences. Under the direction of Carpentry Division Head Joe Padilla, an Isleta Pueblo Indian, his students drafted plans, while other scholars laid the concrete foundation. The use of a Native architect is a singular achievement in Indian Boarding School history. Student-faculty hands-on participation saved the government one-fourth of the total construction costs of $40,000.

The facility opened in 1931, providing living space for single and married AIS employees, with spacious rooms, bathrooms shared by two suites, a lounge, and a huge dining room. The structure later housed offices of the Southern Pueblo Agency. Local people remember shared activities with the building’s occupants, attending events such as receptions after the presentation of a cantata, “The Nativity,” in the auditorium.

But for the children, this single place holds all their memories–learning service trades in the dining room, and especially of annual AIS Proms. Ninety-eight-year-old alumnus Agnes Shattuck Dill says about her school, “I really missed it. I would visit every Sunday. It was heartbreak when the school closed, it was like losing a home.” Agnes and her slightly younger sisters still visit the site, to recall learning to bus trays, and to reminisce about their glittering Proms. Former students note that AIS was a place of pride and identity. Its demolition left a terrible sense of loss, disconnectedness, and grief.

The Employees’ Building at the Albuquerque Indian School represents a bygone era, an faddish architectural style, seldom seen but still evocative of another time, a place of service and celebration, Native education in America, a smaller, more involved community, and the integration and acceptance of the First Americans. This place matters.

By Mo Palmer, published author, local historian, archivist.