Albuquerque's First Church

A Brief History of the Buildings of San Felipe Neri

by Richard Ruddy

by Richard Ruddy

On what might at first seem a rather dreary fall afternoon, about the year 1910, Albuquerque photographer William Walton set out to capture on film the San Felipe Neri Church and rectory. It was a labor of love, letting the late afternoon light shape the building and using tree shadows and the absence of people to help convey mood. He was not deterred by, and indeed welcomed, a cloudy sky and was delighted, I’m sure, by a moment of sunlight that made a range of tones possible from nearly black to nearly white. When he first saw the negative, still wet from processing, he must have been thrilled. He would have known he had a powerful image of a building that had been photographed dozens of times but rarely like this—not dreary but tranquil, not just a photographic document but an emotional statement (figure 1).

It is not surprising that San Felipe Neri Church was, and is, so often photographed. It is surely the iconic building of Albuquerque, photographed thousands of times every year by tourists and locals and featured frequently in Chamber of Commerce literature. San Felipe was Albuquerque’s first church, originally named for St. Francis Xavier perhaps to curry favor with the viceroy in Mexico City who was the Duke of Alburquerque, don Francisco Fernandez de la Cueva Enriquez. Although the viceroy ordered the name changed to San Felipe, in deference to King Phillip V, locals continued to refer to their church as San Francisco. Ostensibly, they were uncertain about which San Felipe was correct. Was it San Felipe the Apostle or San Felipe Neri, the Italian saint. The San Francisco Xavier name persisted until there was an official ecclesiastical visit in 1776 by Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguez, who clarified the problem. Thereafter, at the insistence of Dominguez, the church was correctly referred to as San Felipe Neri.[i]

The original church (1706-1792) was on the west side of the plaza and facing east. A good description of the first church by Dominguez provides a reasonable idea of how the church, the compo santo (cemetery) and rectory were laid out.[ii] Like all adobe structures, the church needed constant maintenance, perhaps more so for this large and more complex building. By the early 1790s it was clear the original church was so overwhelmingly in need of repair that it simply collapsed. Construction on the new church was begun in 1793.[iii] The new church remains standing and in use today, facing south from the north side of the plaza with the rectory stretching east from the church.

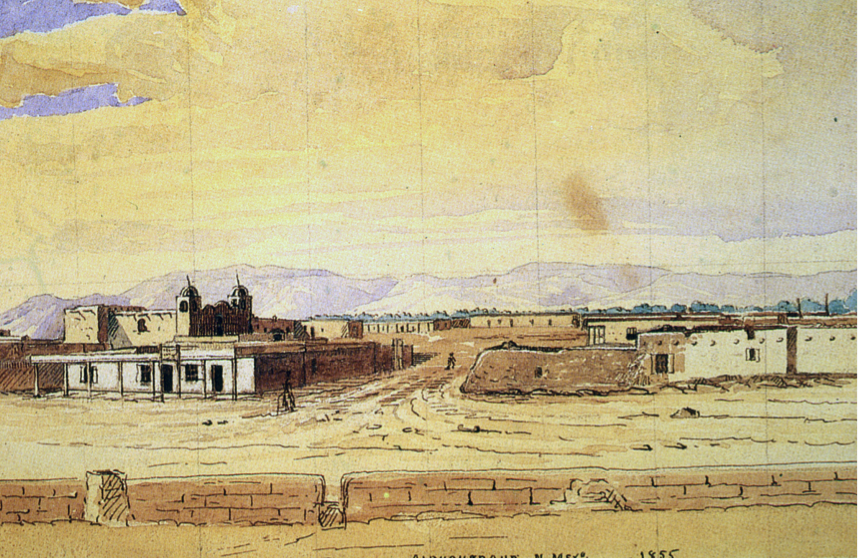

The first known rendering showing San Felipe was an illustration by a U. S. Army Captain Joseph Eaton, made for El Gringo: New Mexico and Her People, by W.W.H. Davis, first published in 1857. The book illustration was taken from a small painting by Eaton now in the Albuquerque Museum archives (figure 2). Significantly, the painting shows the twin bell towers of the church constructed of what we can reasonably assume was adobe.[iv] Fray Angelico Chavez suggested the two towers were much like the belfries on the church at Acoma Pueblo.[v]

The first known rendering showing San Felipe was an illustration by a U. S. Army Captain Joseph Eaton, made for El Gringo: New Mexico and Her People, by W.W.H. Davis, first published in 1857. The book illustration was taken from a small painting by Eaton now in the Albuquerque Museum archives (figure 2). Significantly, the painting shows the twin bell towers of the church constructed of what we can reasonably assume was adobe.[iv] Fray Angelico Chavez suggested the two towers were much like the belfries on the church at Acoma Pueblo.[v]

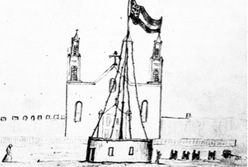

Figure 3: Sketch of San Felipe Neri Church, 1862. Artist unknown. Image courtesy of the Albuquerque Museum

Figure 3: Sketch of San Felipe Neri Church, 1862. Artist unknown. Image courtesy of the Albuquerque Museum

With New Mexico officially becoming a part of the United States in 1850, major changes were on the way for the entire territory including San Felipe Neri Church. On August 9, 1851 Jean Baptiste Lamy approached Santa Fe from the south after an arduous six-month journey that took him from Cincinnati to New Orleans, across a stretch of the Gulf of Mexico and eventually to San Antonio, El Paso and north to Santa Fe. Several miles from Santa Fe his party was met by thousands of people including Territorial Governor James Calhoun. They had come to welcome the first Catholic bishop to reside in New Mexico. He would bring enormous change to the Catholic Church, change that was not always welcomed.[vi]

Bishop Lamy may have influenced the first significant alteration to the exterior of San Felipe Neri, the reconstruction of the bell towers, probably completed within a year or so of 1860. Fray Angelico Chavez suspected that the new “gothic towers” were the work of a French carpenter named Folanfant.[vii]

The new twin towers are notable in an extant 1862 sketch by a Confederate soldier (figure 3). The sketch shows the guardhouse in the plaza at that time flying the Confederate Stars and Bars flag with San Felipe and its new belfries in the background. Historian Father Thomas J. Steele also notes the presence of a picket fence in front of the church in the 1862 sketch.[viii]

Bishop Lamy may have influenced the first significant alteration to the exterior of San Felipe Neri, the reconstruction of the bell towers, probably completed within a year or so of 1860. Fray Angelico Chavez suspected that the new “gothic towers” were the work of a French carpenter named Folanfant.[vii]

The new twin towers are notable in an extant 1862 sketch by a Confederate soldier (figure 3). The sketch shows the guardhouse in the plaza at that time flying the Confederate Stars and Bars flag with San Felipe and its new belfries in the background. Historian Father Thomas J. Steele also notes the presence of a picket fence in front of the church in the 1862 sketch.[viii]

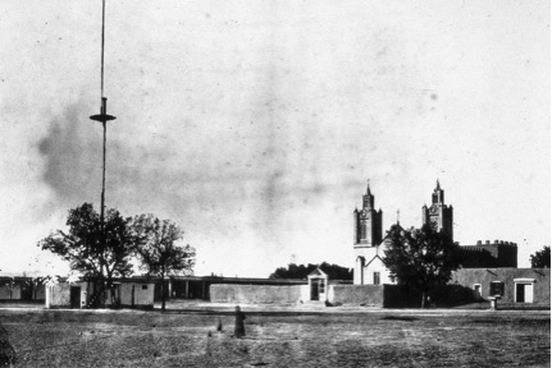

Figure 4: Alexander Gardner photo of Albuquerque, 1867. Image courtesy of the Albuquerque Museum, (94.1.1) and Missouri History Museum (F-13848, plate 065)

Figure 4: Alexander Gardner photo of Albuquerque, 1867. Image courtesy of the Albuquerque Museum, (94.1.1) and Missouri History Museum (F-13848, plate 065)

One of the first photos of Albuquerque was shot in 1867. Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner, working for a survey crew plotting possible rail lines, is credited with the image, a print of which is in the files at the Photo Archive at the Albuquerque Museum (figure 4).[ix] In the five years between 1862 and 1867, a wall appears enclosing the church cemetery (a compo santo) that had not been used for many years. The cemetery wrapped around from the front of the church to the west side. According to Father Steele’s research, by 1872 the exhumation of bodies from the campo santo was complete, the bodies reburied east and north of the church across Mountain Road with some bodies removed to the Santa Barbara Cemetery at Edith and Indian School Rd.[x]

It should be noted that the 1793 church was built on property that was part of the plaza, thus reducing the size of the plaza. The structure on the left side of the photo is a U. S. Army guardhouse with an impressive 121 ft flagpole. The original church (1706) was located on the street directly behind the guardhouse (to the left of this picture).

It should be noted that the 1793 church was built on property that was part of the plaza, thus reducing the size of the plaza. The structure on the left side of the photo is a U. S. Army guardhouse with an impressive 121 ft flagpole. The original church (1706) was located on the street directly behind the guardhouse (to the left of this picture).

The most dramatic changes to the church came with Jesuit priests recruited by Archbishop Lamy on a visit to the Vatican in 1867. Lamy had been impressed with the work done by Jesuits in Tucson and specifically requested priests and brothers of that order. Three priests and two bothers returned with him, Fathers L. Vigilante, Rafael Bianchi and Donato M. Gasparri and Brothers Prisco Caso and Rafael Vezza.[xi] They began their duties at San Felipe in May 1868. An article in an Albuquerque Journal Magazine in 1984 claimed that Lamy was “out of step with the Spanish Southwest. He distrusted Hispanic priests and disliked the adobe parish churches and native religious folk art.”[xii]

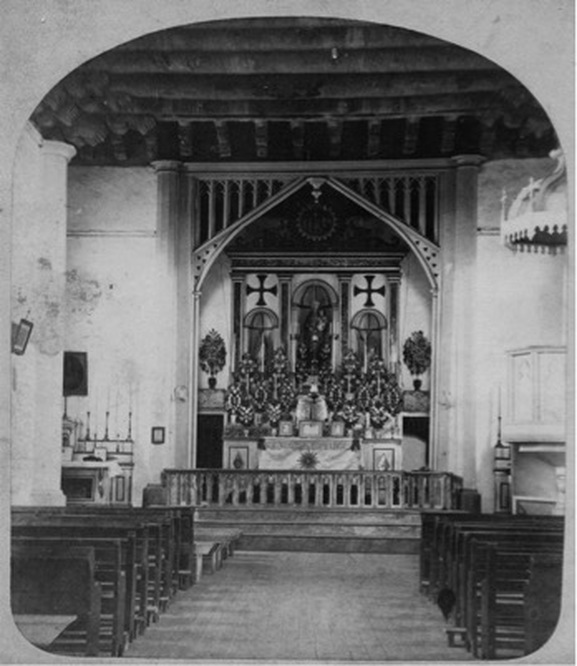

Over the many years Jesuits were at San Felipe, they slowly converted the interior and, to a lesser extent, the exterior of San Felipe to conform as best they could to the Italian Baroque style they knew so well. Some of the “improvements” included a new main altar, removing the humble altar screen and replacing it with triple niches for display of Italian made statues. They hard plastered the walls making the uneven adobe surfaces flat and straight and painted them white. They added or enlarged windows and built side altars made of wood. They painted all the wood altar surfaces and the elevated pulpit to look like marble. They made new confessionals and added three sacristy rooms to the east wall of the church. They propped up the choir loft with two pillars and added a new door and steps to the front of the church. They replaced the roof with more reliable corrugated tin, a product unavailable in Albuquerque before the coming of the railroad (1880). In 1883 they took delivery on statues of San Felipe Neri and San Francisco Xavier. Today the altar features San Felipe Neri in the honored position in the middle, flanked by St. Francis Xavier on the left and St. Ignatius Loyola, patron saint of Jesuits, on the right. In 1891, they added a second story to the rectory.

An interior view of the church (c. 1881) shot by a photographer named W. P. Bliss, shows many of the changes already accomplished by the Jesuits (figure 5). Interestingly, the tin ceiling and curved trusses of today’s church were not yet installed; the original ceiling of vigas and corbels were not yet hidden as they are today.

Over the many years Jesuits were at San Felipe, they slowly converted the interior and, to a lesser extent, the exterior of San Felipe to conform as best they could to the Italian Baroque style they knew so well. Some of the “improvements” included a new main altar, removing the humble altar screen and replacing it with triple niches for display of Italian made statues. They hard plastered the walls making the uneven adobe surfaces flat and straight and painted them white. They added or enlarged windows and built side altars made of wood. They painted all the wood altar surfaces and the elevated pulpit to look like marble. They made new confessionals and added three sacristy rooms to the east wall of the church. They propped up the choir loft with two pillars and added a new door and steps to the front of the church. They replaced the roof with more reliable corrugated tin, a product unavailable in Albuquerque before the coming of the railroad (1880). In 1883 they took delivery on statues of San Felipe Neri and San Francisco Xavier. Today the altar features San Felipe Neri in the honored position in the middle, flanked by St. Francis Xavier on the left and St. Ignatius Loyola, patron saint of Jesuits, on the right. In 1891, they added a second story to the rectory.

An interior view of the church (c. 1881) shot by a photographer named W. P. Bliss, shows many of the changes already accomplished by the Jesuits (figure 5). Interestingly, the tin ceiling and curved trusses of today’s church were not yet installed; the original ceiling of vigas and corbels were not yet hidden as they are today.

Figure 7: Interior of San Felipe Neri, ca. 1903. Photo by G. Daniel Miller courtesy of the Albuquerque Museum

Figure 7: Interior of San Felipe Neri, ca. 1903. Photo by G. Daniel Miller courtesy of the Albuquerque Museum

Architect Thomas L. Lucero and historian Father Thomas J. Steele believe the curved trusses and the tin ceiling that hide the vigas and corbels, were installed by two Jesuit brothers in 1916.[xiii] However, a photograph dated 1903 in the archives of the Albuquerque Museum, show the trusses in place at that time (figure 7).

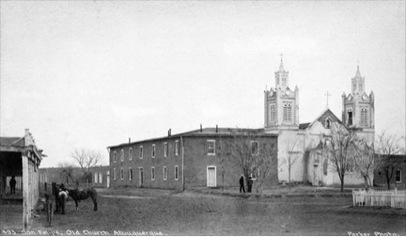

Figure 8: Exterior of San Felipe Neri, ca. 1890. Photo by Parker Landscape Photographers, San Diego, CA. Photo courtesy of Nancy Tucker.

Figure 8: Exterior of San Felipe Neri, ca. 1890. Photo by Parker Landscape Photographers, San Diego, CA. Photo courtesy of Nancy Tucker.

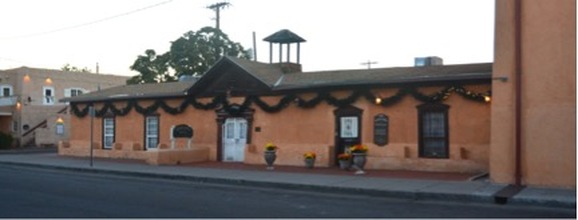

This brief discourse would not be complete without a discussion of the building attached to the west side of San Felipe; the convent, school and wayfarers home of the Sisters of Charity built about eight years before this photo was made by a San Diego photographer named Parker (figure 8).

After a number of unsuccessful attempts at establishing schools in Albuquerque’s Old Town in the 1860s and early 70s, in 1878 the Jesuits were able to acquire the property to the north of the church and all along what we know today as Church Street. In the Parker photo (figure 8), a portion of a single story building can be seen just behind the sisters’ convent. This was Our Lady of Angels School for Boys built on the newly acquired property. The school began operation in December, 1878.[xiv] Today it is leased out as an art gallery (figure 9).

The two-story convent and school for girls was under construction by early May of 1881 and was ready for use by the sisters on September 21. Classes began on November 2, 1881.[xv] A nine-page paper issued by San Felipe Parrish, undated and unsigned, said the name of the school in the convent building was Loyola Hall. An 1882 notice in the Albuquerque Journal announced that the “School of Our Lady of Angels, under the direction of the Sisters of Charity will re-open Monday, September 4, 1882.”[xvi] It would seem the sisters had taken responsibility for the education of both the boys and girls. The coed school exists today as San Felipe Elementary located southeast of the plaza. It should be noted that in 1882 the nuns received twelve dollars per month each in public funds and accepted all children. It was therefore Albuquerque’s first public school.

The account of the construction of the two-story convent is rather murky. Father Steele’s research indicates the building was completed before the sisters arrived to take possession of it. A popular account of the construction gives a great deal of credit for construction supervision to Sister Blandina Segale, one of the first Sisters of Charity to teach at the school. Indeed, Sister Blandina may have been involved in the construction. In her memoirs she says that Father Gasparri asked her to take charge of the project. There had apparently been problems with a corner of the building collapsing. Sister Blandina—her account dated September 21, 1881—hired an unnamed Italian stonecutter to come down from Santa Fe to lay “a stone foundation.” Although dated Sept. 21, she may have been referring to work done earlier that summer. If she means an entirely new foundation, that would suggest a early stage of construction and would mean she was in Albuquerque much earlier than Sept 21. Without better documentation, we can only speculate. That Sister Blandina was a remarkable person there is no doubt. She is currently under consideration for canonization by the Catholic Church, the first time for such an honor in the 400 years of Catholic history in New Mexico.[xvii]

The account of the construction of the two-story convent is rather murky. Father Steele’s research indicates the building was completed before the sisters arrived to take possession of it. A popular account of the construction gives a great deal of credit for construction supervision to Sister Blandina Segale, one of the first Sisters of Charity to teach at the school. Indeed, Sister Blandina may have been involved in the construction. In her memoirs she says that Father Gasparri asked her to take charge of the project. There had apparently been problems with a corner of the building collapsing. Sister Blandina—her account dated September 21, 1881—hired an unnamed Italian stonecutter to come down from Santa Fe to lay “a stone foundation.” Although dated Sept. 21, she may have been referring to work done earlier that summer. If she means an entirely new foundation, that would suggest a early stage of construction and would mean she was in Albuquerque much earlier than Sept 21. Without better documentation, we can only speculate. That Sister Blandina was a remarkable person there is no doubt. She is currently under consideration for canonization by the Catholic Church, the first time for such an honor in the 400 years of Catholic history in New Mexico.[xvii]

Figure 10: Romero Street, Old Town, 1881. In the distance the single story Our Lady of Angels School can be seen. Just beyond it is the convent under construction. Frequent standing water in Old Town no doubt contributed to foundation problems at the convent. Photo courtesy of the Nancy Tucker Collection.

The buildings of San Felipe Neri are a treasure for all people of Albuquerque. They account for an entire square block of Old Town and remind us of our rich history. There are purists who think San Felipe should be restored to its original state, but that would be to deny the blending of cultures that have made San Felipe Neri what it is. Its history is readily seen even in its architecture. Today it remains a vital Catholic parish with parishners whose families have been here for many generations, who cherish their friendships with relative newcomers (figure 10).

Afterthought

To only write about the buildings of San Felipe Neri Church is to ignore the much larger story of the church, the story that incorporates the people who were associated with it in the more than three hundred years of its existence. But to write this larger story, and to do it well, is to undertake a major project that would likely include years of research. So, for now I have taken this narrow approach and hope that it stimulates others to undertake a more detailed account of the people and events associated with San Felipe Neri. Undertaking such a story will surely not disappoint.

-- Richard A. Ruddy, August 2016

-- Richard A. Ruddy, August 2016

Notes:

[i] Steele, Thomas J. Works and Days: A History of San Felipe Neri Church, 1867-1895. (The Albuquerque Museum, 1883). Page 26; also Simmons, Marc, Hispanic Albuquerque: 1706—1846. (University of New Mexico Press, 2003) Pages 67-68.

[ii] Lucero, Thomas L. and Steele, Thomas J. Religious Architecture in Hispano New Mexico (LPD Press, Albuquerque, 2005). Pages 32-34.

[iii] Steele, 26-28.

[iv] Davis, W.W.H. El Gringo: New Mexico and Her People, (University of Nebraska Press, 1962), Page 344. Note that El Gringo was first published in 1857 by Harper, New York.

[v] Chavez, Angelico. Article in a booklet for the rededication of Santa Felipe Neri in 1972. (San Felipe Neri Parish) page 8.

[vi] Horgan, Paul. Lamy of Santa Fe, (Weslyean University Press, Middletown, Connecticut, 1975). Pages 108-09.

[vii] Chavez. Page 9.

[viii] Steele, page 70

[ix] Photo courtesy of the Missouri History Museum, Plate No. 065, Alexander Gardner Collection.

[x] Ibid, page 74

[xi] Horgan. Pages 337-38

[xii] Johnson, Byron and Sharon. Impact, Albuquerque Journal Magazine (Jan. 10, 1984) pages 8-11.

[xiii] Lucero and Steele. Page 22

[xiv] Steele. Pages 97-98.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Segale, Sister Blandina. At the End of the Santa Fe Trail (Bruce Publishing Company, Milwaukee 1948). Pages 183-85.

[xvii] Ibid. 187-88

[i] Steele, Thomas J. Works and Days: A History of San Felipe Neri Church, 1867-1895. (The Albuquerque Museum, 1883). Page 26; also Simmons, Marc, Hispanic Albuquerque: 1706—1846. (University of New Mexico Press, 2003) Pages 67-68.

[ii] Lucero, Thomas L. and Steele, Thomas J. Religious Architecture in Hispano New Mexico (LPD Press, Albuquerque, 2005). Pages 32-34.

[iii] Steele, 26-28.

[iv] Davis, W.W.H. El Gringo: New Mexico and Her People, (University of Nebraska Press, 1962), Page 344. Note that El Gringo was first published in 1857 by Harper, New York.

[v] Chavez, Angelico. Article in a booklet for the rededication of Santa Felipe Neri in 1972. (San Felipe Neri Parish) page 8.

[vi] Horgan, Paul. Lamy of Santa Fe, (Weslyean University Press, Middletown, Connecticut, 1975). Pages 108-09.

[vii] Chavez. Page 9.

[viii] Steele, page 70

[ix] Photo courtesy of the Missouri History Museum, Plate No. 065, Alexander Gardner Collection.

[x] Ibid, page 74

[xi] Horgan. Pages 337-38

[xii] Johnson, Byron and Sharon. Impact, Albuquerque Journal Magazine (Jan. 10, 1984) pages 8-11.

[xiii] Lucero and Steele. Page 22

[xiv] Steele. Pages 97-98.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Segale, Sister Blandina. At the End of the Santa Fe Trail (Bruce Publishing Company, Milwaukee 1948). Pages 183-85.

[xvii] Ibid. 187-88